Land Man

In Danish the word for farmer is landmand, or “land man.”

My father-in-law Villy is truly a man of the land, descended from multiple generations of famously laconic farmers who cultivated flat, marshy land under cold gray skies in a remote part of West Jutland, Denmark. For over half a century he tended his own small farm, which supported his wife and children. His entire life was his land; he spent most of his time within its confines, caring for his buildings, fields, and beloved animals. Any free time was spent socializing with other farmers. He did not want or need anything else.

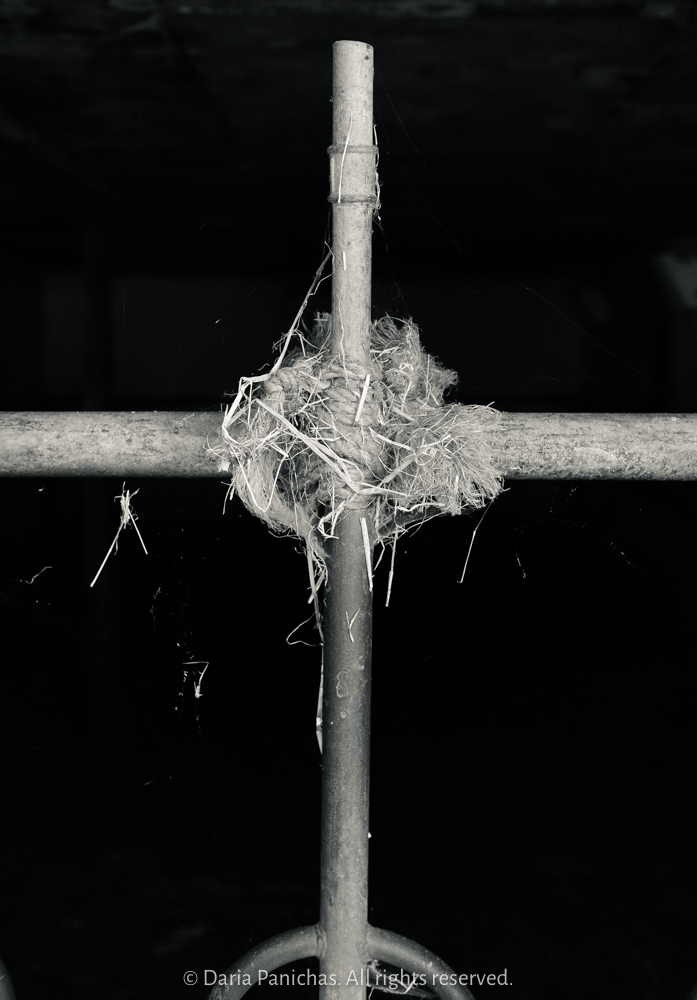

During these decades Villy sustained a number of serious work injuries, including fractured ribs, snapped tendons, a punctured lung, a broken back. He had three hip replacements. Still he worked, ever-dedicated, never complaining. As he approached his 80th birthday he walked slowly and used a small scooter to get around his land. His right hand functioned poorly; his knees and shoulders barely turned, and it was hard for him haul hay, bend down, reach things, tie his shoes. Yet what he lacked in dexterity he made up for with a surprising, bullish strength. Unable to properly make repairs as he had in the past, he cleverly patched aging systems with whatever was at hand. He constructed elaborate, scrappy webs of wood and rope that both held things in place-—doors, hay, fences, cows-—and also provided anchors for him to cling to, like the spiders that began to take over neglected corners. Eventually he rented a few fields to other farmers and reduced his herd to a handful of sheep and cows. In place of his once-mighty irrigation system that had served acres, he strapped small plastic containers to a walker and watered plants with a dipper. He steadfastly refused to retire.

In the spring of 2021, just after he turned 80, Villy became seriously ill and spent nearly two months in hospital and rehabilitation. At the height of his illness he experienced intense hallucinations. His visions were of animals and tractors, and farms on fire.

In his absence, family and neighbors pitched in to care for his farm, but it was not possible for everyone to pick up Villy’s strings no matter how elaborately he had tied them. It also became clear that he would not recover well enough to work as had had before. After one short, classically understated conversation, Villy agreed to let his son sell his remaining cows. When he finally came home, his barns were empty and his life as a farmer was over.

Made a couple of months after his return, this series documents the last vestiges of Villy’s life work and the life force that went into making it all possible. It was strange to me to see the empty space, the juxtaposition of order and disrepair, how quickly spiders and mold had taken over. Yet Villy’s webs still held the musty hay in place. The big animals were gone, but fusty corners quietly pulsed with tiny life: mice, birds, and bugs, a few scrubby cats, a hedgehog that he continued to visit.

It would be easy, even expected, to see these images as evidence of decline and decay, depressing symbols of aging and inevitable death. However in them I see life that flows against all odds, a bottomless well of adaptiveness and resilience, and one man’s dignified dedication to doing what he knew how to do in whatever way he could, no matter how small, for as long as possible.

Click on the images for a larger view and slide show.